The Saga of Seattle’s Leif Erikson Statue (continued)

Subsequent minutes from the League indicate differing opinions on whether the statue should portray Leif Erikson as a savage warrior with weapons or as a peaceful man. They settled on a version of him as a scout finding a mysterious new land called Vinland. The ax in his hand was an afterthought.2 Werner had depicted Leif Erikson in earlier works wearing a winged helmet, but in this case he explained the wingless helmet, saying “it lends itself to sculpture…it is lofty and points upward.” A shield was eliminated due to cost and the mechanics of casting. Werner’s notes conclude: “I propose to model a man first of all.” The promotional and fundraising material all report that the statue was to be created in Norway.

Funds were raised in many ways: benefit bazaars, dinners, dances, donations, the sale of postcards, loans from both individuals and organizations, gifts in kind, etc. Several committee members, including Captain Gunnar Olsborg, took out loans on their homes to come up with the funds.3 The group raised $40,000, although a debt continued on loans until several years after the statue had been erected.

The first request for permission to give the statue to the people of Seattle and place it in a public park was made to Mayor Gordon Clinton on February 19, 1959. The Park Department opposed the idea, as it would set a precedent for every group that might want a statue in a park.4 Nakkerud then went to the Seattle Arts Commission. They were not interested, but he was relentless. They objected that the statue should not be placed at the new civic center as the League requested, but instead it should face water in the Viking tradition.

Another reluctance was a “chicken and egg” dilemma. Should the Commission insist on seeing the finished product and then consider a site, or could they approve an outdoor sculpture without knowing the setting? The Commission’s John Detlie explained: “If the statue is a fine work of art, we should proclaim it to be so to the city, the nation, and to the world. Such a statue could be installed anywhere, (even) in the middle of the city.”5 At another meeting, a member suggested that the Commission should “get off the pedestal and stop acting like gods in heaven … [for] a sincere effort. We’re not going to get a Michelangelo or Rodin,” while another member muttered, “No, but we should try.”6

At the Commission’s request, the League came up with a 4-foot model, approved at a special League meeting in August Werner’s studio on Sunday, October 30, 1960. At that meeting, President Nakkerud also appointed Edvard Mehlum and Professor Werner to look for a suitable place to have the larger statue made. The Art Commission was also invited there to see it. After their viewing and the Seattle Port Commission’s agreement to accept the statue and place the Viking looking out to the sea, the Art Commission accepted it. Nakkerud’s persistence and protracted dialogue had paid off.

Final approval from the Port of Seattle was received on February 25, 1962, three years after the statue was first formally proposed. According to Seattle Times reporter Lois R. Guzzo: “As for Ericson [sic], his voyage across the Atlantic was a pleasure cruise compared to the difficulty he has experienced in finding his way to Elliott Bay.”7

The League packed up the model for Berkeley, where the Greek sculptor Spero Anargyros increased Leif’s size from four to 16 feet. (Some newspaper articles report the height as 17 feet, and some give it as both 16 and 17 feet in the same article.) Franco Vianello, 24, an artisan from Venice, Italy, then cast Leif in bronze through the “lost wax” process, a 2,000-year-old method. The casting cost $10,000, but afterward, Vianello reported that his inexperience with such a large project kept him from bidding it at the real cost of $15,000. 8 The granite base was constructed by Askim Stenhuggeri, south of Oslo, for around $2,000, but was shipped for free. The League reported that the statue cost $42,000 but was worth $72,000 because of the countless hours donated by hundreds of individuals. 9

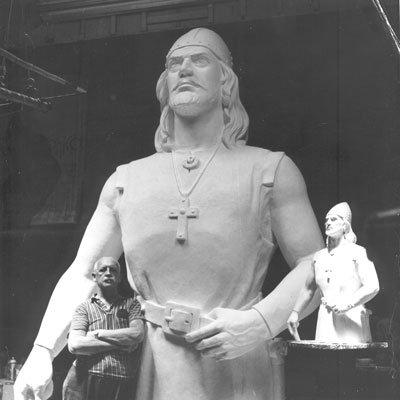

August Werner with the 4-foot model for the Leif Erikson statue

to the right, and the full sized plaster model, cast in 1962.

The 4-ton statue left Berkeley on May 10, 1962, and was unveiled on Norway Day, June 17, at the “Century 21” Seattle World’s Fair. The combined height of the statue and its base was 30 feet. The honor of unveiling it went to Icelandic poetess Jacobina Johnson. John M. Haydon, a commissioner of the Port of Seattle, accepted the statue on behalf of the community. Capt. Gunnar Olsborg was Master of Ceremonies.

Three thousand people watched as numerous dignitaries spoke, including Paul Koht, Norwegian ambassador to the United States representing King Olav V and the Norwegian people. Consul Koht called the memorial “a tribute to a daring and courageous man.” In a nod to Washington’s Italian governor, Albert Rosellini, Koht added, “We must acknowledge that another gentleman who came to this country later than Leif Erikson may have contributed something as well.”10 The Rev. Burton W. Smith, pastor of Ballard’s First Lutheran Church, said that the impressive statue was dedicated “in the memory of one who was willing to risk his life for the unknown and unseen.” He called upon God to let the memorial stand as a “constant reminder of faith, courage, vision.” Speaking on “Leif Erikson the Discoverer,” Dr. Sverre Arestad, professor in the University of Washington’s Scandinavian department, described Erikson as a symbol of the whole Viking Age, A.D. 800 to 1050.11 Governor Rosellini, Mayor Gordon Clinton, Icelandic Consul Karl Fredrick, Norwegian Consul Christen Stang, and others spoke. Professor Werner directed the Norwegian Ladies and Norwegian Male choruses.

That evening, Ambassador Koht gave Norway’s highest honor, the Saint Olav award, to Nakkerud and others, including Paul P. Berg, Frode Frodesen, the Rev. O.L. Haavik, Andrew J. Haug, Edward T. Mehlum, Henry Ringman, and P.D. Wick, for their duty and service to Norway.

The Leif Erikson League was not content to rest on its oars. On May 2, 1968, King Olav V of Norway visited the statue and paid his respects. Even though the King’s visit was planned for daytime, the League prepared for it by requesting and receiving extra lighting on the statue, particularly for the backside so that the plaques there could be viewed.

The League continued its advocacy on behalf of Leif Erikson, proposing: a national Leif Erikson Day, proclaimed by President Johnson on October 9, 1964; a postage stamp issued on October 9, 1968; and a commemorative plate issued on October 9, 1978.

They also got the statue placed on nautical maps. That effort started with several independent Norwegian ships saluting the statue by blowing three long whistles, the first within hours of the unveiling. Nakkerud took up his pen and by mid-1963, Washington Senator Henry M. Jackson announced that Leif Erikson was on the maritime charts.12